Singapore has an efficient G. We pride ourselves on spending the least, proportionally, on things like education, healthcare, while still attaining good outcomes compared to other nations. We run a good system, so we think, because it ticks all the KPI boxes that we measure – cost, ratios, outcomes.

But are there hidden costs involved?

Mr. Always Late

My personal pursuit of efficiency comes in many forms. One of these is that I love cutting my timings close – deadlines, meetings, appointments. The result is that I am often late for meetings. This suits my personal measure of “efficiency” just fine – I hardly waste a minute waiting for other people as I am the last to arrive. I am very efficient in that sense.

The cost, hidden from my calculation, is other people’s time. If I hold up two people for five minutes, I have gained five minutes at the cost of a 10 minute loss to them. The loss doesn’t come on my tab, so why should I care? But the fact is that the group/society/system as a whole becomes more inefficient even as I gain efficiency.

The cost of my tardiness is socialised, and it doesn’t bite me in the back until much later, and I may never realise that it may be precisely my tardiness that knocks on – maybe 100 degrees of separation later – to work out as low quality service from my waiter at a meal, which I hate.

A chat with a friend online (and a lunch with another) also surfaced this thought – that costs that aren’t socialised at the national level could be socialised at other levels, and often these costs are somewhat hidden, and almost always unquantified.

Who pays for an individual’s bad choices?

What one friend raised was family problems. We got down to talking about how bad choices by one or more members of a family had an outsize effect on the other members of the family (in the SG context) because the state/society held to a strict policy of insisting that when an individual makes a bad choice, his family must pay for it first.

Is it better for four people to pay for one person’s burden, one out of every five times (one bad actor in one out of every five families of five persons) or for 96% of people to pay for 4% bad actors?

I’ll not debate the merits of socialising bad personal choices (poor money management, habits like gambling, or neglect and irresponsibility) here. My point is that just because we are not spending it out of the national budget, does not mean that Singapore doesn’t pay for it. Broken families, debt shouldered by the rest of the family, lowering the productivity of otherwise-productive family members – all these are unquantified effects and costs of allowing a family to pay for mistakes of one of its members first, before society steps in to help.

So here’s a question for our philosophy of mandating that family members pay first for the needs and/or failures of their kin: The numbers look great on paper, but what’s the drag on society as a whole?

Who pays for welfare?

Another example is how our social welfare system depends heavily on private funding. To describe the Singapore system simplistically, the G spends a tiny amount to fund some social welfare initiatives. The rest of the burden is placed on VWOs, some of which are fund-matched by the G.

The VWOs provide ground-feel and have a mandate to be extremely efficient with their funds (because they do not suffer from the “big pockets” psychology that the G might have). They also help to galvanise engagement of individuals with charity work, often within a given social framework – business/religious/race.

Some of my friends praise this use of VWOs – they ideologically believe that there should be no or little mandated social welfare: Citizens in a nation have no/low baseline responsibility to provide living basics for one another via taxation. Bleeding hearts should pay first, and wealthy bleeding hearts before everyone else. Singapore’s VWO-reliant system allows those with means and will (well-off and/or bleeding heart) to bear a disproportionate burden. If you are poor or selfish, you do not need to carry the burden, but the 250% tax exemption creates an incentive for those that are selfish and rich (assuming they cannot find another way to avoid taxes).

One unmeasured side-effect of this is how tapping on private money and labour for social welfare may actually take private funding away from other areas of social development that the state should not engage in (or engage too much in). The arts, sports, culture, media, civil rights – in other countries such initiatives are often backed by foundations and trusts, or other privately funded organisations.

In Singapore, the pressing need for VWOs to fund basic standard of living means that priority is taken away from these other social pursuits. Whether this is by design, I’ll not speculate here.

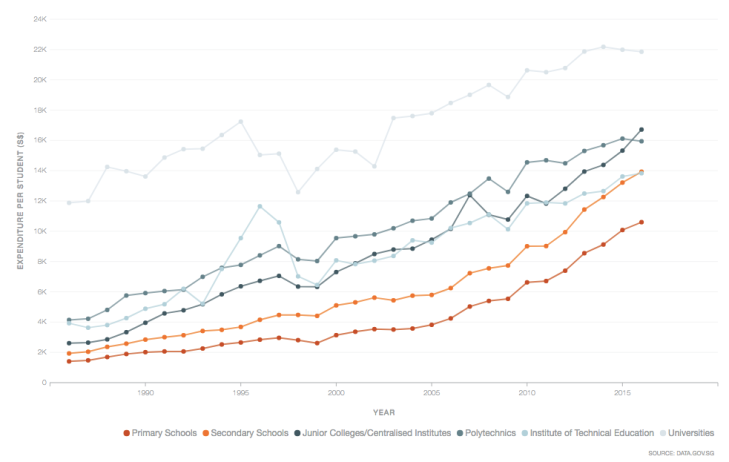

Who pays for education?

I was asked again today about whether the Finnish education system would be better for my kids. My answer is “yes”. It’s not that the Finnish system has better measurable outcomes (Singapore consistently ranks marginally higher on PISA, and Finland spends more than Singapore per capita). With six kids, I’ve come to realise that it is very difficult to ensure good outcomes for all my kids as a whole.

Not only is the school system stressful for them, in order to achieve optimal/individually maximised outcomes, our family has to spend resources for tuition, enrichment, etc. It is simply not possible with six children. The cost of education is passed on to children and parents and teachers who are over-stressed. The “system” is efficient – spending and outcomes look great. The people outside of the measurement pay the price – a billion-dollar tuition industry, teacher attrition, and student suicides.

In conclusion

In conclusion, Singapore is a society/state that has, for better or worse, decided that we would not want to socialise many of our costs at the top level. We allow costs to trickle down.

We need to be conscious of this choice and this effect and, based on that awareness, decide anew how much and how we want to socialise costs, and measure “efficiency”.